Sundance Film Festival 1999 Identity Trailer Series

Excerpt from Come to Life

I led a team of aspiring filmmakers from the Sundance Film Festival’s Technical Department in creating three promotional identity trailers for the 1999 festival event. This rare and prestigious commission, green-lighted by Robert Redford and shot on 35mm film, was the culmination of a decade of my time working for Sundance in several different capacities including Festival Runner, Print Traffic Department Coordinator, Film Presentation Manager, Sundance Resort Projectionist and Film Critic. My time with Sundance was very special, offering unprecedented access to the emerging world of independent film and filmmakers, coinciding with some of the most exciting developmental years in the festival’s history. The experience was a direct inspiration towards my ability to formulate and implement the Supernova Digital Animation Festival in 2016 for Denver Digerati as a new, exciting niche to explore through a distinguished festival construct. The materials below include quality transfers direct from 35mm film of the trailers as well as a snapshot of associated materials from proposal to marketing.

Amended in 2025 with Eulogy for Robert Redford at the end of this section.

Come to Life

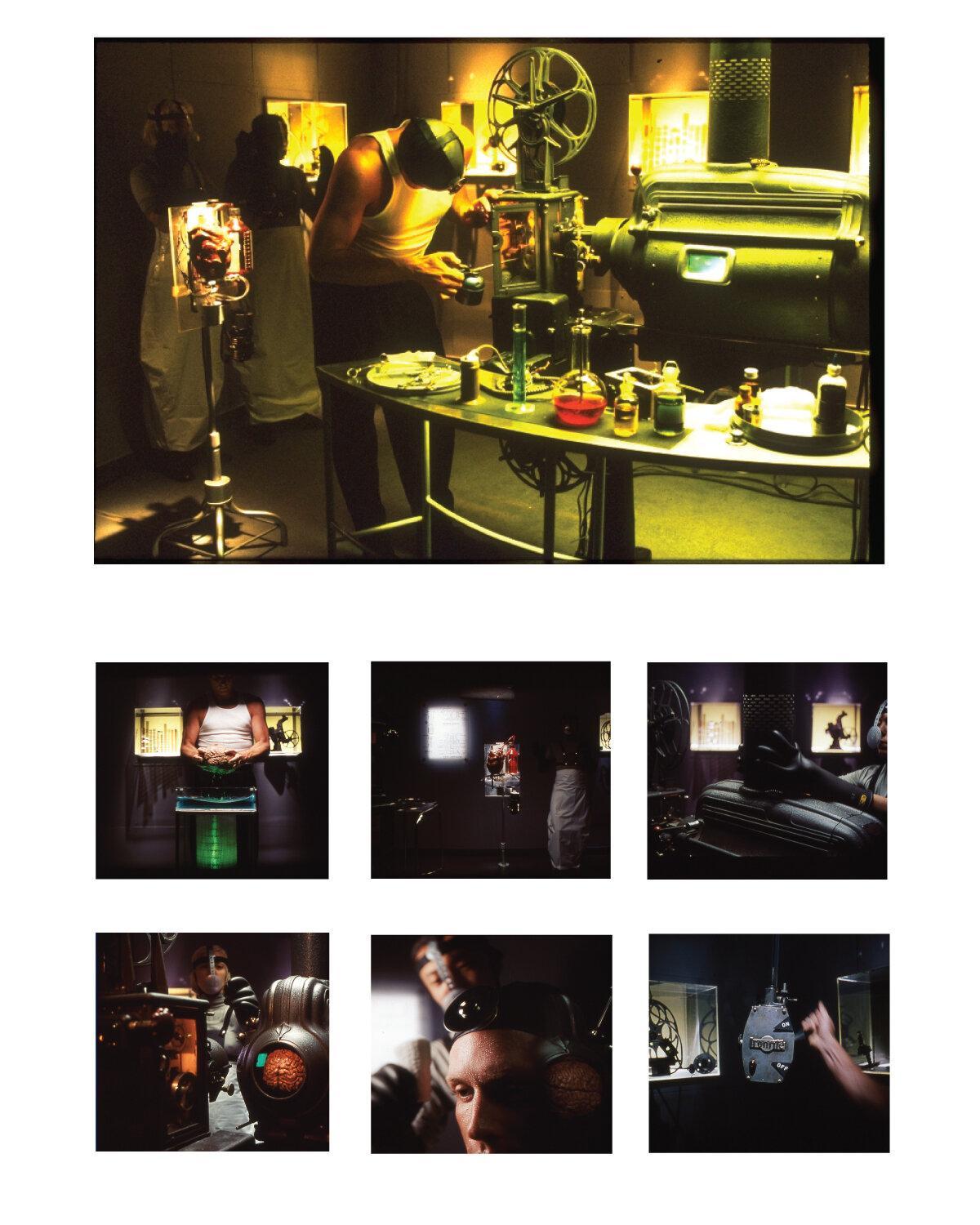

Come to Life was an elaborate constructed set piece with numerous props, shot inside my warehouse studio in Salt Lake City as the first of three trailers to be presented at the Sundance Film Festival, all centered around an old and defunct Motiograph H-7500 carbon arch movie projector as the focal character within all three. The perfectly preserved 35mm projector was a rare find, obtained at Deseret Industries, the prominent local thrift store conglomerate that serviced the state of Utah. Click the image above or watch the full short film HERE

Wish you were here

Wish you were here was filmed at key locations inside Salt Lake City proper and several well beyond in the greater Utah landscape. The Motiograph H-7500 takes on a different character in part two of the series, one reflecting on its exciting, at times daunting time on earth, concluding with a sense of rebirth. Our crew had to haul to each location and build the extremely heavy projector, all within a schedule that optimized light, crew availability and the whim of the elements. Click the image above or watch the full short film HERE

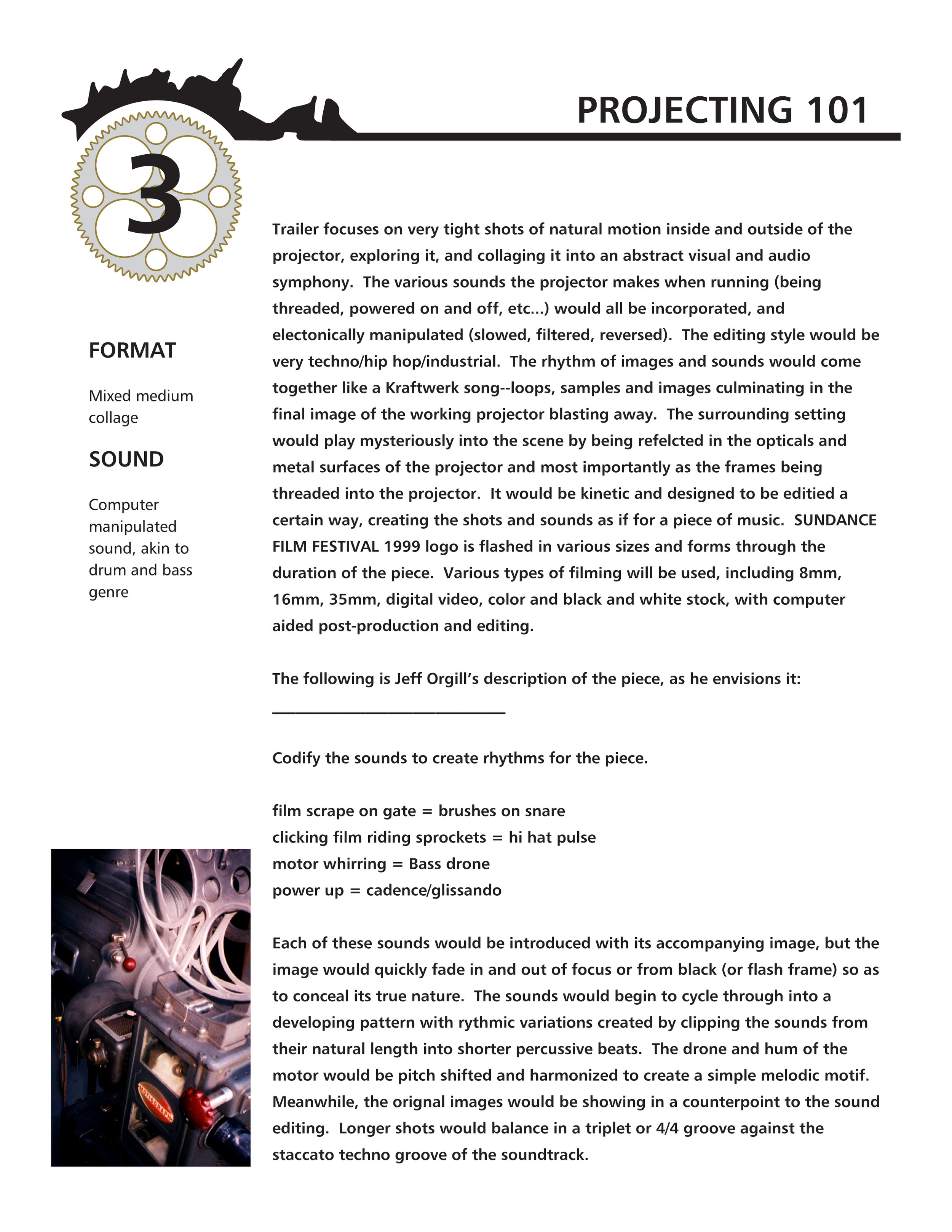

Dream Factory

Dream Factory was the most radical and experimental of the three part trailer series. Short entirely in Jeff Orgill’s apartment studio in Los Angeles, CA, the film takes viewers inside the guts and complex mechanisms of the Motiograph H-7500, shot with micro lenses that allowed for tight spaces and impressive results. The projector is deconstructed into specific compartments, all built sets, in which 35 mm film flows in order to deliver its imaginative imagery to audiences. Click the image above or watch the full short film HERE

Select Materials from the Sundance Trailer project archive

Email was a relatively new tool for communication at the time of the Sundance trailer project. My associates Jeff Winograd, Jeff Orgill and I all lived in different states during our time working at the Sundance Film Festival, only coming together in January for ten days each year. Our correspondence and formulation of a proposal for the project materialized as an interesting study for the use of this new method of communication and idea-sharing. I kept the significant portions of the dialogue intact for future reference, not knowing exactly how this form of communication would fully transform the future.

“Wish You Were Here” trailer stills

“Come to Life” trailer stills

“Dream Factory” trailer stills

1999 Sundance Film Festival Trailer Series promotional postcard for “Wish You Were Here”

1999 Sundance Film Festival Trailer Series poster for “Come to Life”

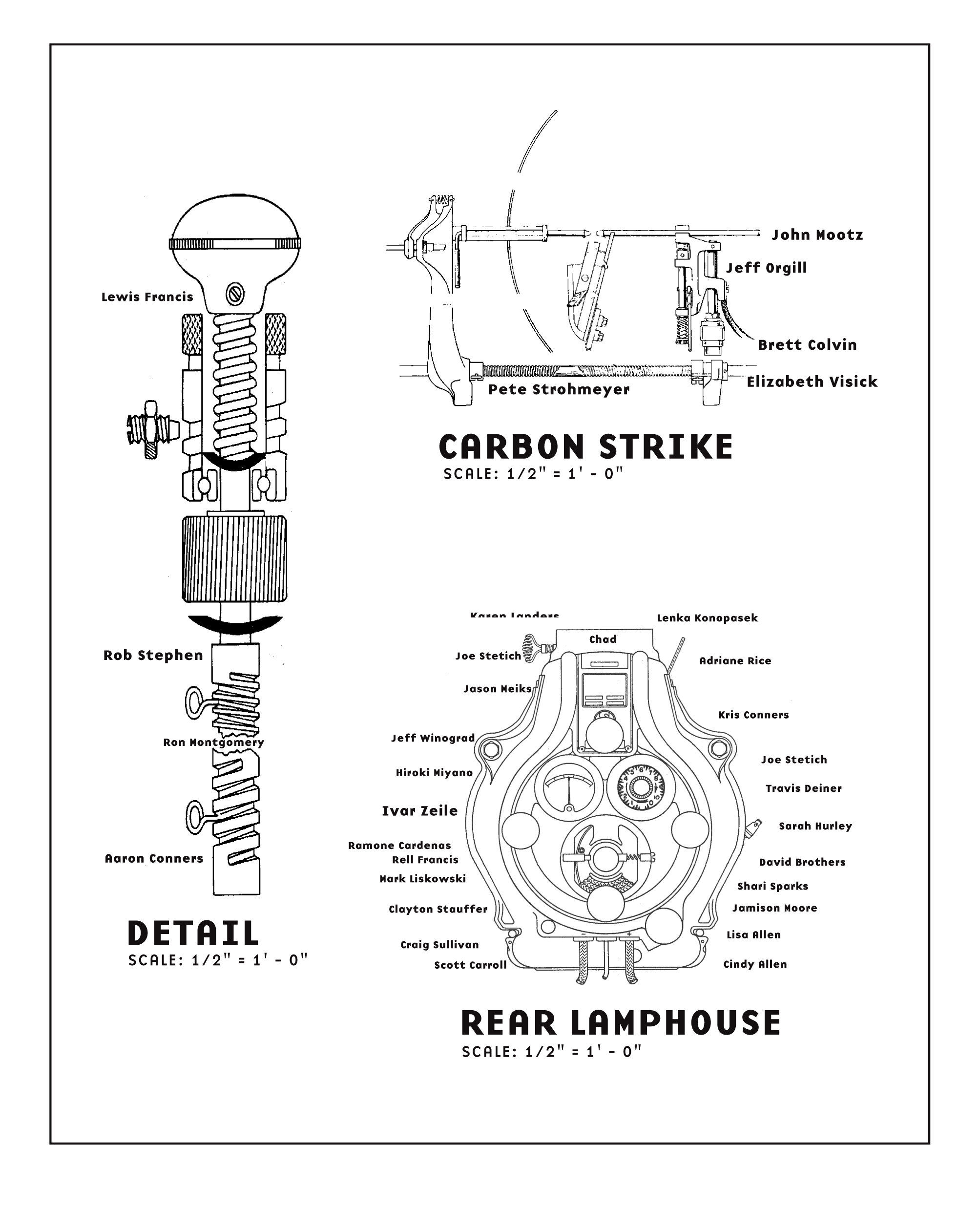

1999 Sundance Film Festival Trailer Series credits graphic, based on projector elements central to the concept

Graphic for auxiliary exhibition hosted by Bibliotect in association with 1999 Sundance Film Festival Trailer Series

Eulogy for Robert Redford, the Boss of it all / September 16, 2025

“I was born with a hard eye,” he told The Hollywood Reporter in 2014. “The way I saw things, I would see what was wrong. I could see what could be better. I developed kind of a dark view of life, looking at my own country.” - New York Times on the passing of Robert Redford, September 16, 2025

Everyone seems to want to influence the world, particularly these days. Robert Redford was one of few to do so in his own way and with exceptional gravitas. My extended stay within the world he created through the Sundance Film Festival was one of the greatest influences on my life. I was fortunate to begin my intersection at the time in which the festival’s reputation would catapult from 0 to 60 in a flash, commencing the year before Sex Lies and Videotape would elevate Sundance to mythic status in the film world, yes the one spanning the entire globe. For every Sex Dog / Reservoir Witch / Blaire Clerks project, or early Brad Pitt vehicle, there was, for me at least, a Gaspar Noe, Clair Denis, Corey McAbee, Rob Tregenza, Jon Jost, Shinya Tsukamoto or Vincent Gallo spectacle to be savored, filmmakers achieving a presence far on the fringes of the culture, where the most interesting material always lurked. I was one of incredibly few who had full access to any and all screenings, but my favorites were typically the ones with plenty of seats available. Through Sundance I became a “film snob,” or as I like to refer to it, a cinephile.

That’s me on the far left, Shinya Tsukamoto second from right, and Hiroki Miyano my incredible DP for the trailer series on the far right, reveling at a Sundance Festival Party.

His friends called him Bob, his legion of volunteers called him Redford. I wasn’t his friend but did get to meet him a couple of times, and have him sign off on a commission for his festival, a rare coup for a no-name guy like me to fantasize about. I would eventually be able to boast about serving as his personal projectionist, which was true, at Sundance resort for several years. My further boast about getting his stamp of approval to create a three part series of promotion trailers for his festival would be my proudest moment of the 20th century. I was one of a trio to achieve that status, the ringleader of a three member team I culled from the depths of the technical department. The other two were angling for careers in film, like everyone else gathering up the mountain each year. I intuitively felt I might excel in the director’s, writer’s and producer chair for a stint so cool, just another venture I wasn’t specifically qualified for to add to all the others that had somehow worked out so far.

This commission would take me to the pyramids, find me floating above the ground in a sea of balloons over Park City, stranded in the desert threatened by a biker gang, as well as surging through a cascading sea of metal and celluloid, in a fish tank of sorts. I would also come face to face with a Frankenstein monster of my own creation, within the small warehouse bunker I resided in, just large enough to build a mad scientists laboratory. Little of this was of much consequence to few outside the scrappy, amazing volunteer team we’d assembled to support the production, all eager to support the effort and experience the thrill of shooting 35mm, with color correction courtesy of Disney Studios. But that was plenty enough, the greatest moment I would have throughout my time across Sundance’s sprawling Utah campus. It would have much more influence on my later career, as I moved into dubious territory as an art dealer, somehow dovetailing into a role as a leading curator of digital animation. It was there that Sundance had its most significant, long range impact on me, everything in between suddenly making sense.

Life under Bob was a crucial reason I would have the chutzpah to conceive, launch, program, administer, market and shill for a motion art festival of my own design in support of digital animation, what I considered the most dynamic and rapidly growing niche in motion art. Maybe not the sole reason, but without my connection to Sundance I really don’t know that it would have flown, at least not as far and wide as it did over the course of 7 years, the best and most difficult period of my life. My decade long stint with Sundance, including as Redford’s right hand man at his resort, briefly in the projection booth anyway, alongside his approval of the commissioned bumper series nearly two decades prior was a leading byline in my bio with which I assumed would carry clout with artists I was hoping to attract as eager participants in Supernova. Did any of that make a difference? I have always believed so. Was there more to it than that? Yes, much much more, yet without Sundance it all may never have come to pass. Maybe none of my later distinguished career in the arts would have, and perhaps I’d have been better off not having ever knocked on that door. I wouldn’t trade it for anything in the world, however, save for a few individuals that are/were of utmost importance in my life.

My first face to face with Bob occurred as a result of comically unforeseen tragedy. Our gregarious, rambunctious, too-much-fun loving head of the tech department, our renegade Marlboro Man, landed on the wrong side of life mid festival during the year that our trailer series lit up each and every screen. Horror upon horrors, you simply can’t make that shit up! Endearing to a fault, he had long boasted of his relationship with “Bob,” nobody really believing they could be as tight as Ron made things out to be. Yet sure enough, Redford showed up the day he passed, offering his condolences to our staff, grieving in the basement of Miners Hospital, our annual home away from home for ten days. That moment meant so much to us, removing at least some of the grim mood that would carry through the remainder of that year’s festivities.

The second came shortly after, the most rare occurrence of my life in film by far. As the official Sundance Mountain Projectionist, my duties consisting primarily of sharing “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” almost every weekend as an homage to the man for families staying at the remote resort, I was called up one day to prepare for a very important screening. Redford would be presenting his latest directorial effort“Legend of Bagger Vance” to an audience of one, the studio head carrying his career as a Director, in preparation for its eventual release. This was big, hush hush stuff, a meeting of the minds to assess the first cut. It was a white knuckle situation for me, the kind only someone with experience running film straight from the cans through dual 35mm projectors could understand the gravity of. Sure I’d confidently run such equipment for years, but any mishap or mistake, no matter how minor, could spell my doom! Fortunately it went smooth as silk, I, the man in the booth, impeccably performing my duty. I had neither the heart or opportunity to tell him I thought the film was a dog afterwards. Yes, I was that much of a film snob. But my time at the resort was a period of pure tranquility and bliss, occasionally riding my vintage two wheeled beamer up for an extended stay during the summer producer labs, where I was given accommodation in the most exquisite mountainside homes.

Redford passed at age 89, born the same year as my own father, still very much alive and kicking, his trajectory and circumstances far different than my pops, sharing only a strong work ethic and personal beliefs. I like to think of Bob as a father figure, far more influential to my life and career than my own in almost every single capacity. Sorry dad, but rebellion, concern for diversity, culture and the environment also seem to have tainted my blood.

What will Sundance now become without Redford? One can only guess as of this writing, and I’m kind of glad that he won’t be around to witness it. I have mixed feelings about Boulder, always have. Sure it's beautiful and even carries one of the more interesting film cultures, the kind I like. But I’m not so sure it has the right soul, the kind cultivated in Utah that really made the whole affair work so very well. The decades there were a passage in history I can’t imagine will be replicated ever again, by anyone. I also carry a dark view that the entire world is in the process of losing its soul, perhaps he passed at the most opportune time, his picture perfect life capped for eternity. I wasn’t exactly saddened to hear of his passing, there are far more things to be sad if not downright furious about right now. The news however caused me to immediately reflect on how damn proud I have always been to have co-mingled with this man’s enterprise and life, during the absolute best period in the festival’s history, fantastical experiences and long distant memories too numerous to relate here that I’ll carry to my own grave. I was little more than a brief blip on his radar, but if I could pass along one thing to him in his afterlife, it’s what a privilege to have been associated and what tremendous impact that had on this life of mine, more than a fair bit of his inspiration filtering through in the form of support to others across the arts. - Ivar Zeile

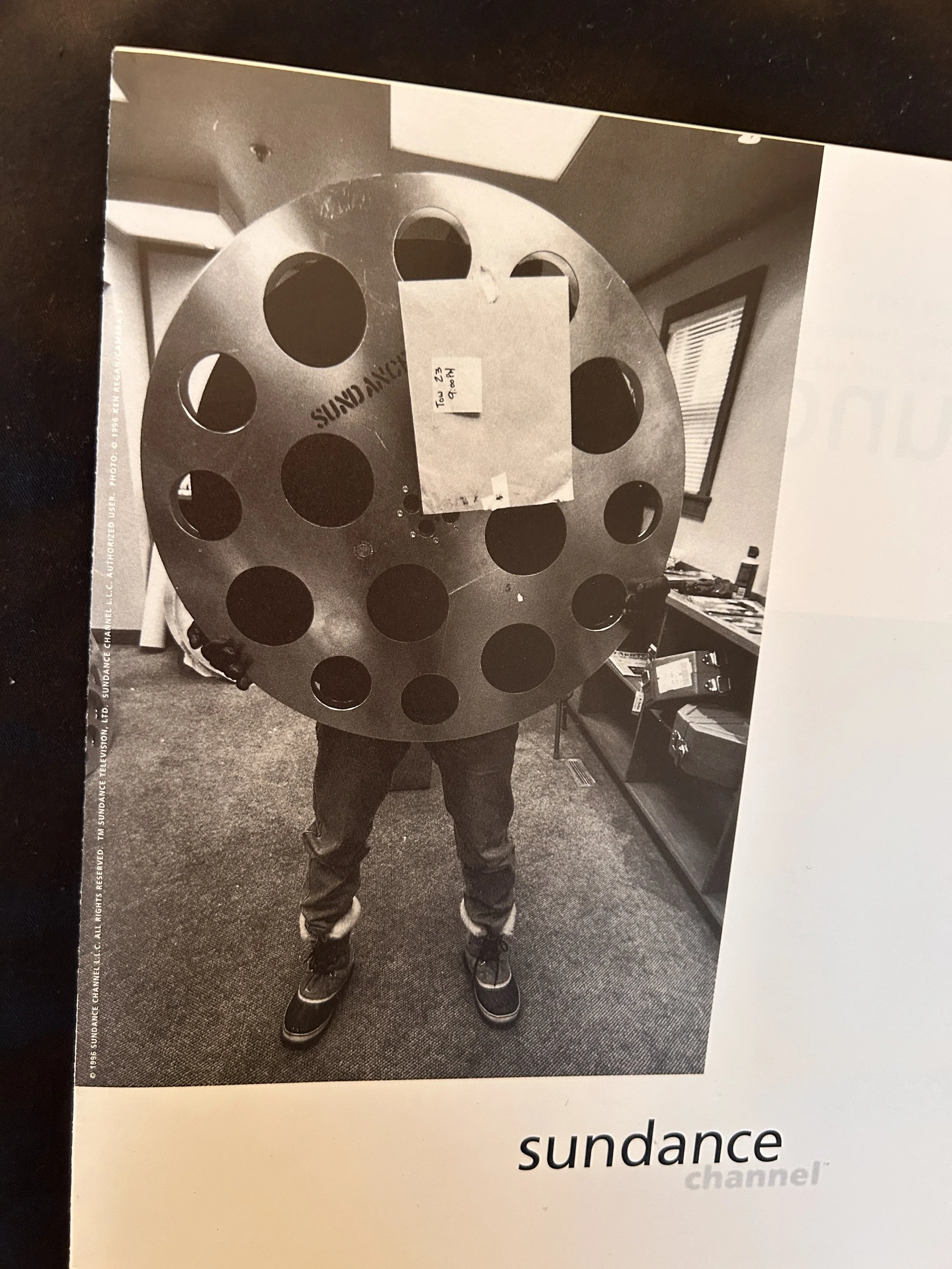

The Sundance Channel emerged near the time of my exit after a decade with the festival. I always loved the cover image they used for their initial promotional materials, featuring my teammate Jeff Winograd holding one of the giant reels of film we moved around the city and mountains each year. The handwriting on the post-it note is mine, a system so basic and effective as to be laughable! Yeah, fuck digital and AI bullshit, this was the heyday of the festival and of independent film, without a doubt!

PROJECT SCRAPBOOK

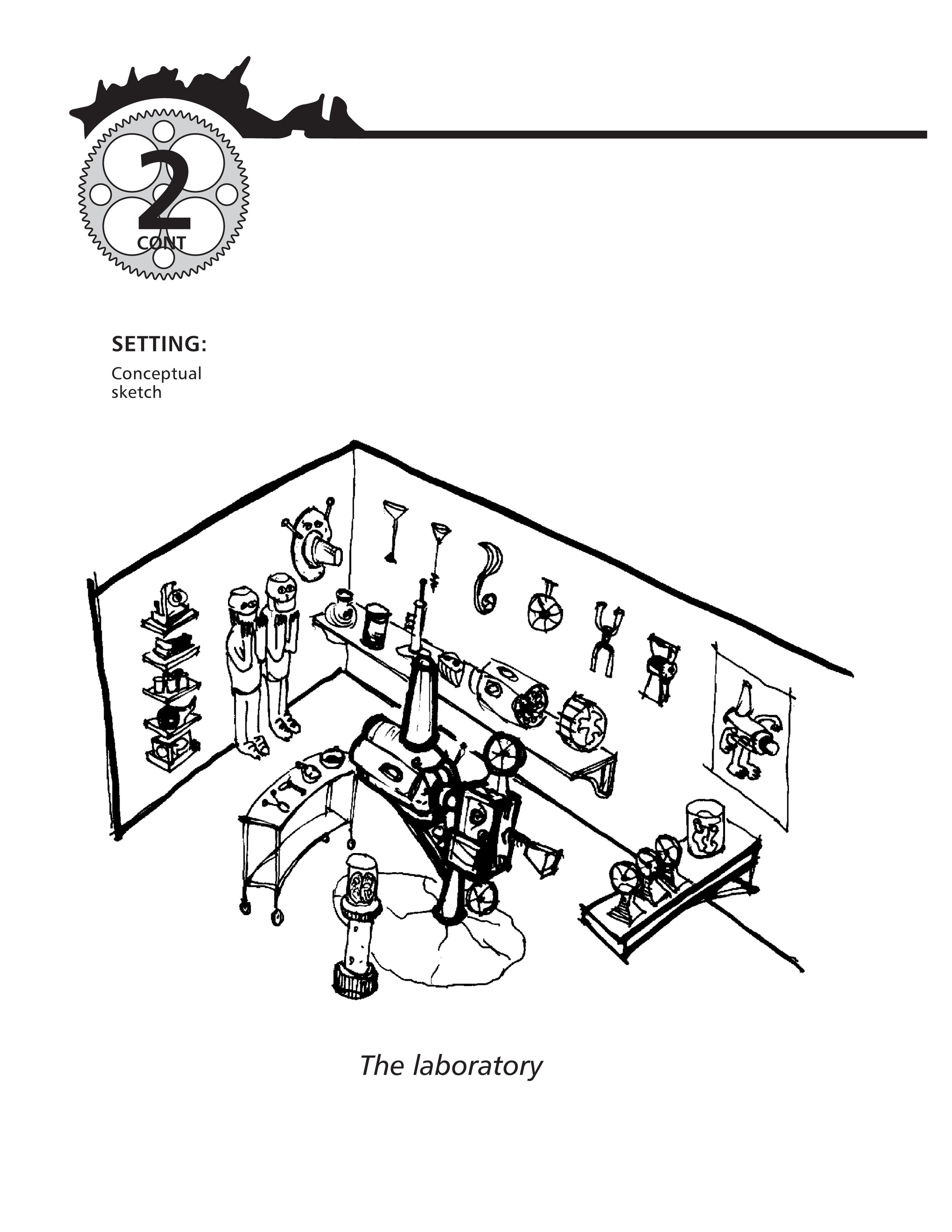

The images below were culled for a display in a small exhibition hosted at the magnificently curated architecture and art focused bookstore Bibliotect, located in SLC’s downtown Art Space block at the time our rare film project was realized, in an attempt to celebrate the process, talent and backstory behind the commission. The exhibition included the Motiograph carbon-arc movie projector as well as props created by local artisans from “Come to Life.” The images were taken the old fashioned way, what I wouldn’t have given to have digital hand-held devices of the 21st century in order to have documented this wonderful undertaking to the degree it had deserved to be captured!

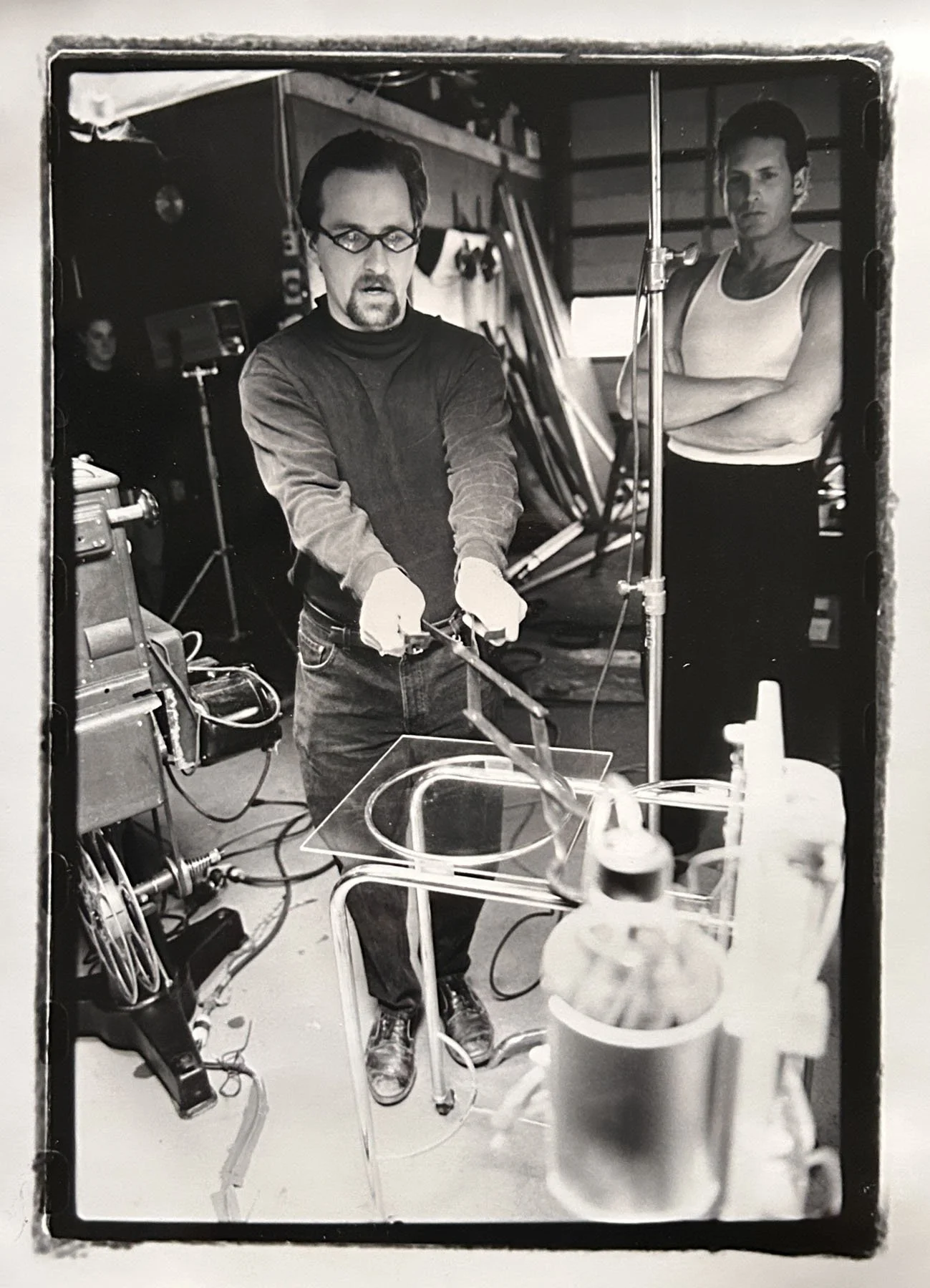

That’s me demonstrating a critical shot on the set of Come to Life, filmed in my warehouse living quarter in SLC.

Hand tinted black and white photo of the Motiograph projector during the rail composition for Wish You Were Here

DP Hiroki Miyano during filming of Wish You Were Here. I could not have been more fortunate that Hiroki was both available and interested in working on the production, my favorite fellow projectionist from my early days at SLC art house cinemas.

Talent on the set of Come to Life during filming

Rigging a prop in my warehouse living quarter where Come to Life was staged and filmed

Generosity of the Park City Balloon club, taking us up for a ride the morning we scouted the concept for Wish you Were Here

Weekend balloon festival held in Park City, where we made connection for the critical and most complex shot in Wish you Were Here.

Derelict Truck Stop on the outer edge of SLC, a great place to shoot without permits for two of the crucial scenes in Wish you Were Here

Faultline Park in SLC, the perfect location for the concluding scene in Wish you Were Here

The Dream Machine set and crew in Jeff Orgill’s LA Studio Apartment

Location scouting polaroids for Wish you Were Here

The Dream Machine set and crew in Jeff Orgill’s LA Studio Apartment

The Dream Machine set and crew in Jeff Orgill’s LA Studio Apartment

The Dream Machine set and crew in Jeff Orgill’s LA Studio Apartment